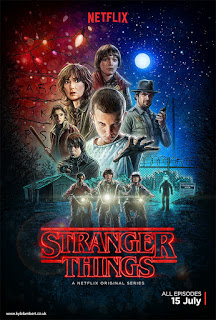

Praise Netflix! The streaming video giant has given those of us poor, middle-aged souls who never quite grew up enough to leave the movies (and games… and comics…) of our youth an incredible gift. The eight-episode series Stranger Things is... well, it’s E.T.! It’s The Goonies! It’s Stephen King’s IT! It’s Stand By Me! It’s Big Trouble in Little China! You name “it” from geek/nerd culture from 1980 through about 1987, and it’s in here somewhere! Oh, and just so the ‘90s don’t feel left out, there’s that hint of X-Files vibe lurking off in the background to boot! Hell, even the poster released to some outlets as a promotional tool is a direct homage to all of those fantastic Drew Struzan one-sheets we all loved in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Okay, okay! What’s it about? The story seems right out of the Steven Spielberg playbook, as 10- or 11-ish year-old Will Byers disappears one night from the fictitious town of Hawkins, Indiana, which sends his single mom Joyce (Winona Ryder, in the show's most obvious nod to the ‘80s), his brother, and his friends and their families into a tailspin as they try to find him.

Eventually they realize something paranormal is going on—especially when the lights in his house seem to start blinking and Mike's sister Nancy's best friend goes missing. There's also a strange girl with a shaved head named Eleven who turns up, for reasons nobody can understand, and Mike and his friends Dustin and Lucas (named, I think quite obviously, for George, the Creator himself) hide her in the basement while they try to figure out how to rescue their friend. There's also the local sheriff (David Harbour), who lives a hermit's life after the loss of his own daughter, and stumbles into the story and knows he has to get involved.

One of the central tenets of Stranger Things is the existence of a plane of existence the boys call “The Upside Down,” a parallel dimension that exists alongside our own, but swaps out decay and death for every bit of life and flourishing on our own plane. Those of us who lived pen-and-paper Dungeons & Dragons can quickly tell you (even if you didn’t ask) that this, along with one of the show's major monsters, is drawn directly from that game’s lore. The show's children—its central characters (who, to the one, are fantastic)—are avid D&D players and, in fact, that's how we meet them: playing a many-hours-long campaign in the basement, and unable to defeat a menacing in-game monster with their powers and rolls of the die.

One of the central tenets of Stranger Things is the existence of a plane of existence the boys call “The Upside Down,” a parallel dimension that exists alongside our own, but swaps out decay and death for every bit of life and flourishing on our own plane. Those of us who lived pen-and-paper Dungeons & Dragons can quickly tell you (even if you didn’t ask) that this, along with one of the show's major monsters, is drawn directly from that game’s lore. The show's children—its central characters (who, to the one, are fantastic)—are avid D&D players and, in fact, that's how we meet them: playing a many-hours-long campaign in the basement, and unable to defeat a menacing in-game monster with their powers and rolls of the die.  Before the eight-hour narrative reaches a conclu-sion, we’ve had mystery, horror, John Hughes-type angst and government Men-in-Black types thrown at us (with Matthew Modine as the main Baddie! - how much more '80s can you get!?!?), and by Jove, it all works! Created by Matt and Russ Duffer, this series perfectly pulls all of its unique stories together into one show. Because this world is so well-constructed, none of these elements stand out as not belonging with the others. That’s a tremendous achievement when you think about how disparate these genres are. The Duffers and their writing staff incredibly give us numerous moments where one spoken word, or one sound effect, or one reaction shot communicates volumes about a character’s motivation or backstory to us.

Before the eight-hour narrative reaches a conclu-sion, we’ve had mystery, horror, John Hughes-type angst and government Men-in-Black types thrown at us (with Matthew Modine as the main Baddie! - how much more '80s can you get!?!?), and by Jove, it all works! Created by Matt and Russ Duffer, this series perfectly pulls all of its unique stories together into one show. Because this world is so well-constructed, none of these elements stand out as not belonging with the others. That’s a tremendous achievement when you think about how disparate these genres are. The Duffers and their writing staff incredibly give us numerous moments where one spoken word, or one sound effect, or one reaction shot communicates volumes about a character’s motivation or backstory to us.

Along with the synth underscore composed by experimental band SURVIVE, the series is peppered with hits from the 1980s, making judicious, thematic use of The Clash’s “Should I Stay Or Should I Go,” which has never had a more chilling effect. You’ll also revel in the evocative use of music from the likes of Jefferson Airplane, Toto, The Bangles, Joy Division and Foreigner.

Stranger Things is probably the highest-profile role Ryder has managed to land in many years, and it calls back to a time when she was mainstream cinema’s “It-Girl.” She’s highly effective as Will’s working-class mom, with the script calling on her to play a woman whose world and grasp on conventional reality has broken down — fuelled by grief and a unshaken belief that her son remains alive.

Stranger Things is probably the highest-profile role Ryder has managed to land in many years, and it calls back to a time when she was mainstream cinema’s “It-Girl.” She’s highly effective as Will’s working-class mom, with the script calling on her to play a woman whose world and grasp on conventional reality has broken down — fuelled by grief and a unshaken belief that her son remains alive.

Ryder’s not the only one bringing in a world-class performance on the show — David Harbour is excellent as the town cop trying to unravel the conspiracy. Even the kids are quite good in a Goonies-esque way as they launch their own investigation, and I can’t begin to describe the beyond-her-years performance of young Millie Bobby Brown as Eleven.

As the series is only eight episodes, Stranger Things is the perfect binge over a weekend. If you haven’t yet caught it, make it the primary project for your next I-Will-Stay-On-The-Couch-This-Entire-Weekend weekend. Don’t just watch it for the nostalgia or the genuine creeps, watch it because it’s compelling storytelling.